One of the greatest pleasures that I have, as an historian, is stumbling upon a piece of evidence that confirms something that we already know from somewhere else.

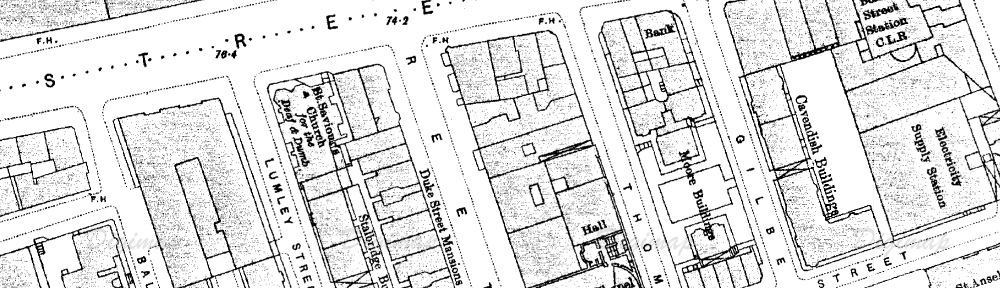

This morning, for example, I stumbled upon this – in a biography of Charles Baker, who was the headmaster of the Doncaster school for deaf children in the 1850s.

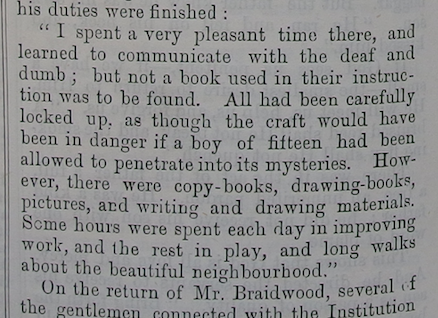

This is a cutting from an 1875 biography of Baker, and it describes a visit that he made to the school in Birmingham run by the grandson of Thomas Braidwood, the famous educator of deaf children.

The Braidwood family were renowned for being extremely secretive about their methods, so much so that when Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet visited London in 1815, the headmaster of the London school (owned by Braidwood, and run by his nephew Joseph Watson) refused to tell him what his method was unless Gallaudet agreed to stay and work for him.

Gallaudet refused, and travelled to Paris instead, where he persuaded Laurent Clerc to leave the Parisian deaf school, and travel to North America. Between Clerc and Gallaudet, they started the American deaf school at Hartford, and the rest… as they say… is history.

Braidwood’s methodological secrecy in London had a direct impact upon the direction that Deaf education in America took. Had he been less secretive, American Deaf education might have turned out quite differently. And here, Baker’s biography gives us confirmation of that secrecy.

It is a real pleasure to find evidence like this that has a direct link to other stories that we already know. It’s like the two stories are just one, that connect… and something amazing happens.

As a historian, it is a bit like watching the scene from Lady and the Tramp (watch from 1 min 15 secs) where Lady and the Tramp pull out the same strand of spaghetti from different ends, and end up kissing.

(I guess you have to really love history to see it like that… but I do!)

The closest we have to a full description of the Braidwoods’ “lost” methodology is in Francis Green’s “Vox Oculis Subjecta,” published in 1783. Green’s son Charles attended the Braidwood Academy in Edinburgh. Unfortunately, he died young. The Abbé de l’Epée is mentioned in the book, so Green may have gone to Paris to observe his school. He continued advocating for the founding of a school for the deaf in North America even after Charles died, and Dr. Mason Fitch Cogswell may have been inspired by one of Green’s pamphlets or the book to push for the founding of “Old Hartford.”

A link:

https://archive.org/details/gu_voxoculissubj00gree

One thing I’ve discovered about the Braidwoods: they were apparently not pure-oralists. (Neither was Heinicke, the great-granddaddy of the rigorous “German Method” or “Pure-Oralism,” but that’s a bit off the point; he used a variety of approaches, some of which strike us as being wacko.) The Braidwoods evidently utilized what we’d call a “Total Communication” approach, using fingerspelling and writing in addition to the usual oral drills. Not sure if they used real sign language, although the pupils likely used it outside of class. But Gallaudet wasn’t impressed by the progress made by Braidwood’s pupils. And there was that insuperable obstacle of their demanding that he sign a contract promising to remain with them four years, not divulge their method, pay a sizable bond to insure compliance with their conditions, etc. They were anxious to protect their monopoly because the dissolute John Braidwood the Younger was, at that moment, trying to found a school in the U.S.—the ill-fated private school at Cobbs being the result.

History is indeed full of ironies.

The Doncaster school was another bastion of pure-oralism, bu the way. After Charles Baker’s death, E. M. Gallaudet, who had met him during a tour of schools for the deaf in the UK and Europe, purchased his impressive library, which became the nucleus of Gallaudet University’s Deaf Collection.